Translate this page into:

Case report – Muir–Torre syndrome – A skin-deep manifestation of underlying malignancy

*Corresponding author: Nazneen Pallikkalakathu, Consultant Medical Oncologist, Department of Medical Oncology, Smita Memorial Hospital and Research Centre, Thodupuzha, Kerala, India. nazneen.noorah@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Pallikkalakathu N, Reddy MC, Pallikkalakathu A. Case report – Muir–Torre syndrome – A skin-deep manifestation of underlying malignancy. Int J Mol Immuno Oncol. 2024;9:116-8. doi: 10.25259/IJMIO_26_2024

Abstract

We report a case of Muir–Torre syndrome in an Indian male patient diagnosed with synchronous malignancy of squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma colon, with a strong family history of gastrointestinal malignancies. Next-generation sequencing revealed germline mutations in Mut S homolog 6. Skin tumors particularly sebaceous carcinoma, sebaceous adenoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and keratoacanthoma serve as cutaneous markers for internal malignancy.

Keywords

Synchronous

Muir–Torre syndrome

Cutaneous markers

Next-generation sequencing

Mutation

INTRODUCTION

Muir–Torre syndrome (MTS) is a rare autosomal dominant genodermatoses that presents with skin manifestations such as sebaceous neoplasms and visceral malignancies. The recognition of their skin findings is important not only for the initiation of appropriate therapy but also for the detection of other associated abnormalities, including malignancy in these frequently multisystem disorders.

CASE REPORT

We present a case report of a 55-year-old male with a history of non-healing ulcer over the left nasolabial fold [Figure 1]. He underwent wide local excision of the lesion and it was suggestive of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma keratoacanthoma type.

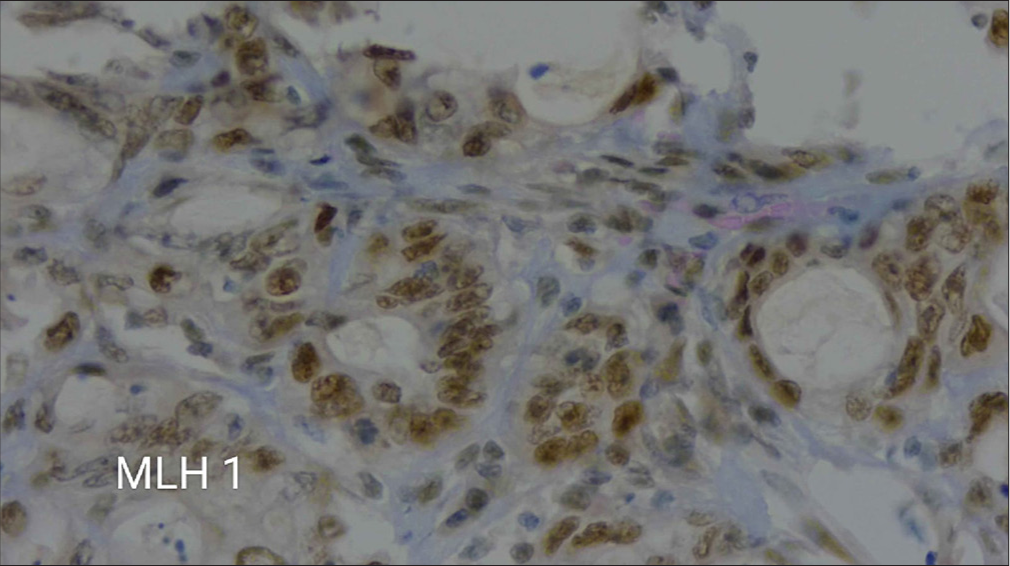

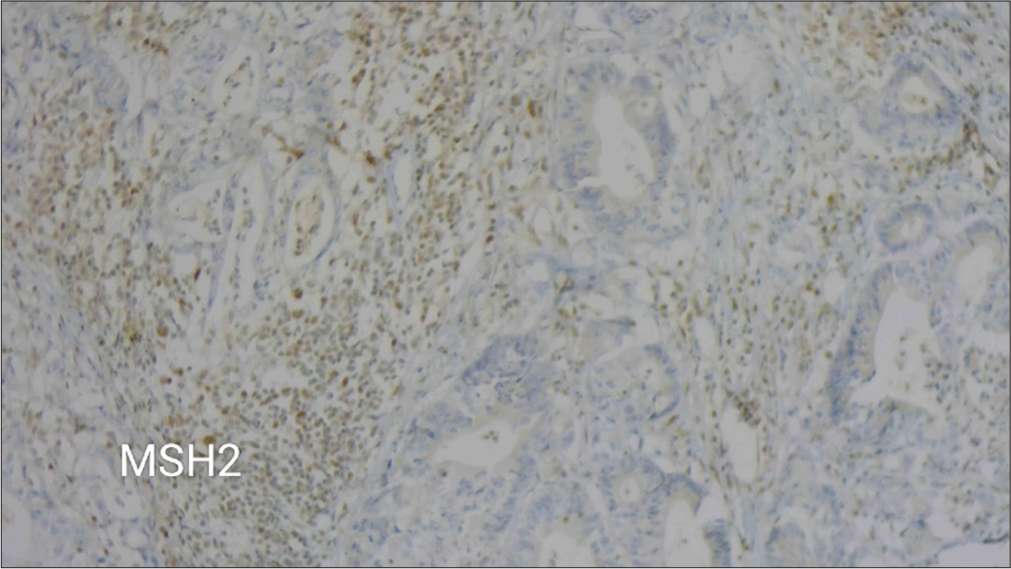

After 5 months, he was again evaluated for right hypochondriac pain. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography abdomen showed a lesion in the colon. A colonoscopy showed an ulcerative lesion in the hepatic flexure. He underwent a biopsy of the lesion, and it was suggestive of adenocarcinoma. His carcinoembryonic antigen was elevated with a value of 6.47 ng/mL. He underwent a right hemicolectomy, and a histopathological examination revealed the colon tumor as a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma with the classification of pT3N0 (American Joint Committee on Cancer; AJCC 8th Edition). Immunohistochemistry showed strong staining of MLH1 [Figure 2] and loss of Mut S homolog (MSH)2 [Figure 3] and MSH6. He gives a family history of gastrointestinal malignancies in his paternal side nephews. He underwent next-generation sequencing, which showed a pathogenic variant in the MSH 6 gene (p. Gly1157Ser).

- Non-healing ulcer over the left nasolabial fold.

- A microscopic view at 40× magnification showing immunohistochemical staining for MLH1.

- A microscopic view at 10× magnification showing weak immunohistochemical staining for MSH2.

The patient was referred to a geneticist for genetic counseling. He was made aware of his elevated risk of acquiring tumors, his family’s history of gastrointestinal cancers, and the significance of routine monitoring and follow-up.

DISCUSSION

MTS is a variant of Lynch syndrome that was first described in 1967 by Dr. Muir and in 1968 by Dr. Torre.[1] It is a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterized by the presence of sebaceous gland neoplasms and visceral malignancies such as gastrointestinal and genitourinary malignancies. The presence of theses tumors should serve as an indication to initiate screening [Table 1].

| Physical examinations | Yearly including breast in women, testicular and prostate in men |

| Laboratory Tests | Full blood count, CA125, CEA, fecal occult blood, and urine analysis |

| Colonoscopy | Every 1–2 years, from age 25 years or 5 years before the youngest age of diagnosis of colorectal cancer in the family, and annually from age 40 years |

| Pelvic examination | Annually in women with transvaginal ultrasonography and endometrial biopsy in patients with a gene mutation from age 25 years |

| Consider gastroscopy | Every 1–2 years in the family with a history of gastric cancer |

| Consider renal ultrasonography | Every 1–2 years in families with a history of renal tract cancer |

| Consider prophylactic colectomy | In patients with gene mutation |

CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen, CA125: Cancer antigen125

The most commonly seen sebaceous tumors in MTS are sebaceous adenomas and keratoacanthomas. The common site for skin lesions is the trunk, but can also be seen on the face. These cutaneous manifestations precede the appearance of internal malignancies. Of the skin lesions associated with MTS, 22% of skin tumors occur as the initial lesion, 6% occur synchronously, and 56% arise after diagnosis of visceral malignancy.[2] Colorectal cancer is the most frequently associated visceral cancer in MTS. Other associated cancers include lung, endometrial, ovarian, parotid, breast, gastric, small intestinal, and hematological. The median age for onset of malignancies is 53 years.[3] MTS is caused by germline variants in the DNA mismatch repair genes and is considered a phenotypic variant of Lynch syndrome. One-third of cases of MTS are caused by mutY DNA glycosylase (MUTYH) variants and may represent a clinical phenotype of MUTYH-associated polyposis, an autosomal recessive polyposis syndrome caused by biallelic pathogenic variants in the base excision repair gene MUTYH.[4] In one study, MutL protein homolog1 (MLH-1) mutations displayed a positive predictive value (PPD) of 88%, whereas MSH-2 and MSH-6 displayed values of 55% and 67%, respectively, whereas the combinations of MLH-1 with MSH-6 showed 100% PPD.[5] These mutations can arise sporadically, and thus history of a corresponding visceral cancer must also be present to make the diagnosis.[6] Recently, there have been some reports of MTS patients developing central nervous system (CNS) tumors. The majority of these cases appear to have occurred years after colorectal carcinoma. Interestingly, MSH-2 was positive in all patients with CNS tumors with the maintenance of normal MLH-1 and had strong family histories of CNS malignancy.[7,8]

Adenocarcinoma of the colon in the setting of MTS tends to be multifocal and occurs almost a decade earlier than in sporadic cases. In addition, the proximal colon is more often affected, compared with unifocal involvement of the distal colon in sporadic cases.

Although there is a lot of published research on MTS, our case study aims to highlight the critical impact of genetics on cancer. This will help pave the way for future genetic mapping of oncological malignancies and increase understanding of the illness. Finding a diagnosis in one patient can save numerous others in this specific situation alone. Genetic testing can help us identify common mutations in these populations and may aid in the development of new targeted treatments. Molecular diagnosis has an important role in detecting patients who are carriers of mutations of the mismatch repair system since such individuals present an 80–100% risk of developing cancer.[9,10]

These mutations should never be overlooked in the modern era, thanks to sophisticated technologies such as next-generation sequencing, which emphasizes the significance of taking detailed history and clinical examination of the patient.

CONCLUSION

The presence of skin sebaceous tumors associated with a personal or family history of gastrointestinal malignancies is very suggestive of MTS, and the biopsy specimen should be immunohistochemically stained to identify the mutated gene, followed by germline testing of the corresponding gene. While similar DNA mismatch repair gene mutations link MTS to Lynch syndrome, MTS can also entail a variety of non-colorectal and non-genitourinary malignancies as well as unique skin manifestations. A comprehensive evaluation of both cutaneous and internal findings is crucial to ensure accurate diagnosis management and prevent the oversight of other malignancies or genetic abnormalities.

The tumors in MTS must be treated by standard methods according to the site of the cancer. Genetic counseling for risk identification and close follow-up for cancer screening is especially important in these scenarios.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript, and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Multiple primary carcinomata of the colon, duodenum, and larynx associated with keratoacanthomata of the face. Br J Surg. 1967;54:191-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir-Torre syndrome: Case report of a patient with concurrent jejunal and ureteral cancer and a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:681-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir-Torre syndrome: Diagnostic and screening guidelines. Aust J Dermatol. 2006;47:266-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MSH-6: Extending the reliability of immunohistochemistry as a screening tool in Muir-Torre syndrome. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:159-64.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer-associated genodermatosis: Skin neoplasms as clues to hereditary tumor syndromes. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;85:239-56.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glioblastoma multiforme as initial internal malignancy in Muir-Torre syndrome (MTS) JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:381-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir-Torre syndrome and central nervous system malignancy: Highlighting an uncommon association. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:856-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]